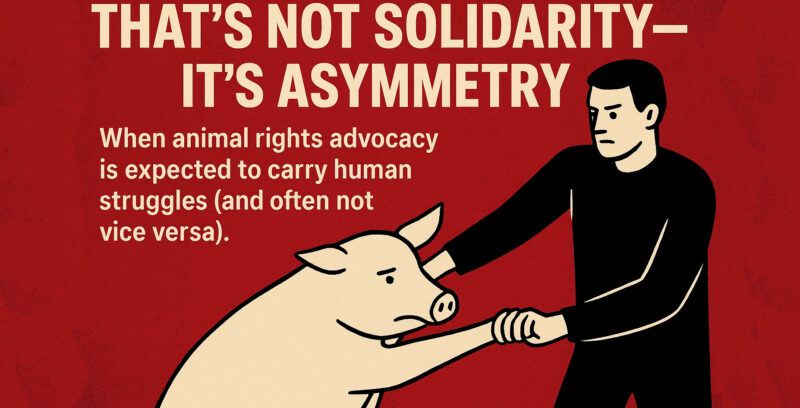

In activist and academic circles, intersectionality is often treated as a moral imperative—a framework that promises to unify struggles and expose overlapping systems of oppression. For many, it’s a way to ensure no voice is left out, no injustice ignored. But when it comes to animal rights, intersectionality reveals a troubling asymmetry: animal advocates are routinely expected to center human issues to be seen as inclusive or legitimate, while human rights movements rarely reciprocate by integrating animal concerns. That’s not solidarity—it’s asymmetry.

Collective Liberation—or Unequal Burden?

The concept of collective liberation is often invoked to justify the expectation that animal rights activists should integrate human justice issues into their advocacy. The idea is that capitalism, patriarchy, colonialism, and speciesism are interlocking systems of oppression—and that activists must forge alliances across movements to dismantle them together. In theory, this is compelling. It promises unity, solidarity, and a shared ethical horizon.

But in practice, collective liberation often functions as a one-way demand. Animal rights activists are expected to center human struggles—whether through labor justice, racial equity, or anti-colonial narratives—to be seen as relevant or inclusive. Meanwhile, their own cause—the liberation of nonhuman animals from systemic use, commodification, and enslavement—is treated as secondary, optional, or even distracting. The ethical clarity of veganism is diluted to serve broader human-centered agendas.

Other movements—labor unions, racial justice organizations, feminist collectives—rarely adopt intersectionality to include animals. Their frameworks already assume a human-centered scope, and their calls for solidarity seldom extend to nonhuman victims. This reveals a structural bias: inclusion is not mutual. Animal rights activists are asked to stretch their ethics across species and systems, while others remain comfortably within anthropocentric boundaries.

This asymmetry doesn’t just burden animal rights activists—it exposes a deeper contradiction in how justice is defined and distributed. If collective liberation excludes those most systematically objectified—nonhuman animals—then it risks replicating the very hierarchies it claims to oppose.

The Dilution of Veganism’s Moral Message

This imbalance places a quiet but persistent pressure on animal rights activists. To gain credibility, they must frame their cause through human-centered lenses—health, labor, colonialism, oppression, trauma. Meanwhile, the true message of veganism—the recognition of nonhuman animals as subjects of moral concern, whose lives have intrinsic value beyond their utility to humans—is often sidelined or diluted. Veganism, at its core, is a moral stance against the systemic use, commodification, and enslavement of sentient beings. When this message is reframed to prioritize human benefit or strategic alliances, the movement risks losing its clarity, its urgency, and its moral foundation.

Ethics Reversed: When the Perpetrator’s Feelings Matter More Than the Victim’s Life

Take, for example, the common argument that slaughterhouse work causes psychological harm to workers. While this is undoubtedly true and worth addressing, it’s often used as a primary reason to oppose animal slaughter. But imagine telling someone to stop hurting women—not because it’s wrong, but because it’s bad for their health. That framing would rightly feel off. It shifts the focus away from the victims and centers the impact on the perpetrator. In animal advocacy, this logic is disturbingly common: “Don’t harm animals because it traumatizes the workers.” Or: “Stop harming animals because it’s bad for your health and the environment.” While these arguments may be factually valid, they displace the ethical core of the issue. The animals themselves become secondary—reduced to instruments for human well-being rather than recognized as beings with their own right not to be used, harmed, or commodified.

Boycotts and the Ethics of Selective Resistance

Consider how political boycotts—such as the boycott of Israeli-supported brands—are widely accepted as acts of ethical resistance. Yet the boycott of animal-based products, which is central to veganism, is rarely treated with the same moral seriousness. In fact, many activist circles that champion human rights boycotts never include animal exploitation in their frameworks at all. This selective application of ethics exposes a troubling inconsistency: violence against humans is seen as politically urgent, while violence against animals remains optional, negotiable, or invisible.

What’s more, some animal rights activists go further: they call for the boycott of vegan products if those products are linked to human rights abuses or genocide. This reflects a deep commitment to ethical consistency across struggles—even when it means sacrificing convenience or symbolic alignment. But the reverse is almost unheard of. Human rights activists rarely, if ever, call for the boycott of animal-based products, even when those products are the direct result of systemic violence, enslavement, and slaughter. It’s a glaring double standard: animal advocates are expected to boycott for humans, but human-centered movements never boycott for animals.

This isn’t solidarity—it’s exploitation of solidarity. The burden of ethical integration falls disproportionately on animal advocates, who are asked to stretch their moral framework to include every human injustice, while their own cause is treated as peripheral, inconvenient, or expendable.

Rethinking Intersectionality Through an Ethical Lens

This asymmetry is not just a strategic concern—it’s an ethical one. If intersectionality is truly about dismantling hierarchies, then it must challenge the human/nonhuman divide with the same rigor it applies to race, gender, and class. Otherwise, it risks becoming a tool for expanding human-centered agendas rather than confronting systemic violence across species.

None of this is to say that solidarity is undesirable. On the contrary, genuine solidarity—rooted in mutual recognition and ethical clarity—is essential. But it must be reciprocal. Animal rights activists should not be expected to dilute their message or reframe their ethics to fit into frameworks that do not make space for nonhuman animals. Inclusion must not come at the cost of integrity.

Final Reflection: Justice Must Be Species-Inclusive

Animal rights advocacy is often expected to carry the weight of every other justice movement—while rarely receiving reciprocal support. This is the unequal burden: animal advocates are asked to boycott for humans, speak for humans, and center human liberation in their messaging. But human rights movements almost never do the same for animals. The solidarity is not mutual—it’s conditional, asymmetrical, and often extractive.

This imbalance doesn’t just distort priorities—it undermines the moral clarity of animal liberation itself. When veganism is treated as valid only when it serves human causes, animals remain trapped in a framework where their suffering is negotiable, their rights optional, and their liberation perpetually deferred.

Animal liberation must be treated as a dedicated, urgent movement—just like other justice struggles that advanced on their own terms. It deserves its own space, its own voice, and its own moral urgency. Not because it’s disconnected from other forms of oppression, but because it’s been historically ignored, minimized, and instrumentalized.

To advocate for animals is not to abandon human justice. It’s to insist that ethical consistency must include those who are most consistently excluded. And that liberation, if it means anything at all, must extend beyond the boundaries of species.

Recommended Reads: Why Vegans Should Focus on Animal Advocacy: Lessons from History and the Urgency Today